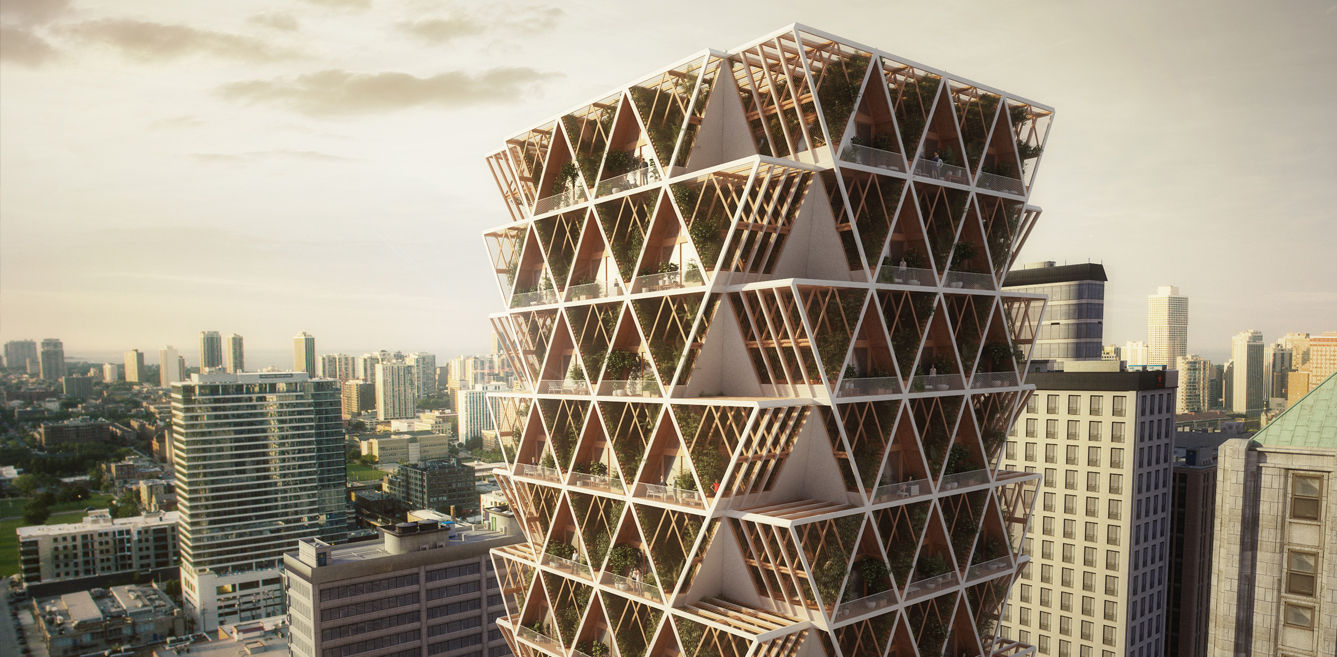

The project is based on a modular building system, developed by Studio Precht, that investigates the connection of people with their food and creates a building that connects architecture with agriculture.

During the last two centuries we became disconnected from our food. But food and shelter are human needs and architects can rethink their relation. There is an opportunity to reconnect architecture and agriculture and change them to the betterment of both. “I think we miss this physical and mental connection with nature and this project could be a catalyst to reconnect ourselves with the lifecycle of our environment,” said Chris Precht. His wife and partner Fei Precht added: “Our motivation for ‘the Farmhouse’ is personal. Two years ago, we relocated our office from the centre of Beijing to the mountains of Austria. We live and work now off the grid and try to be as self-sufficient as somehow possible. We grow most of the food ourselves and get the rest from neighbouring farmers. We now have a very different relation to food. A tomato from your garden tastes different than the one shipped around the globe. We are aware that this lifestyle is not an option for everyone, so we try to develop projects, that brings food back to cities.”

Stacked gardens reduce the need to convert forests, savannahs and mangroves and allows used farmland to naturally restore itself. Vertical farms can produce a higher ratio of crop per planted area. The indoor climate of greenhouses protect the food against varying weather conditions and offers different ecosystems for different plants.

The farmhouse designed by the architects runs on an organic lifecycle of by-products inside the building. Buildings create a large amount of heat, which can be reused for plants like potatoes, nuts or beans to grow. A water-treatment system filters rain and greywater, enriches it with nutrients and cycles it back to the greenhouses. The food waste can be locally collected in the building’s basement, turned into compost and reused to grow more food. “This process of food production becomes visible,” said Precht. “It re-enters the centre of our cites and the centres of our minds. Food is an important part of our daily life and I see ‘the farmhouse’ as an educational statement that it’s no longer a mystery where our food comes from and how it lands on our table.”

The foundation of the farmhouse is to encourage citizens to grow food locally, but it also continues this ecological aspect with its architecture. “In a way, we construct our farmland and we plant our building.” Trees provide the main building material for the farmhouse. Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) panels are used to develop the modular system of structure, finishes and planters. Working with CLT has a lot of benefits. It is precise to fabricate, easy to transport and quick to install. Living with wood has also ecological benefits: Trees grow by a natural source of energy. The process that creates structural engineered wood products takes far less energy than steel, cement or concrete and produces fewer greenhouse gases during manufacturing. Further, wood stores carbon in itself (approximately one tone per cubic meter) thus it has, compared to other building materials, a lighter overall environmental footprint.

The farmhouse consists of a fully modular building system, which is prefabricated offsite and flat-packed delivered by trucks. Prefabrication of a modular building kit shortens the time for construction and its effect on the surrounding. The building system is based on structural clarity of traditional A-frame houses and connects to a diagrid that runs the loads through the building. Each wall of the frame exists of three layers. An inside layer with finishes, electricity and pipes, a middle layer with structure and insulation and an outside layer with gardening elements and water supply.

For single-family structures, this system gives a tool to home-owners to design their own place, based on the needs and the demands to living and farming. Structural and gardening elements, waste management units, water treatment, hydroponics and solar systems can be selected from a catalogue of modules and offers a certain flexibility for various layouts.

The hands-on approach of the DIY movement played a big role in the design. Not only for the gardening part of the building, but also for its construction. This method allows owners to self-construct their tiny houses based on their chosen layout. Architecture that is home-built with food that is home-grown.

Taller structures are assembled as duplex-sized A-frames, which provide a large open space on the first floor for a living room and kitchen and a tent-like space on the second floor for bedrooms and bathrooms. The angled walls give space for gardening on their outside and create a V-shaped buffer zone between the apartments. This also lets natural ventilation and natural light into the building. The building invokes a direct connection with a natural surrounding that stands apart from the concrete landscape of our cities. A tent that is surrounded by nature. A Yin and Yang of colourful gardens and healthy interiors.

The gardens can be used privately for residents to grow their own food, or as a collaborative effort to plant vegetables and herbs for a wider community. After the harvest, the food can be shared or sold at an indoor farmers market on the lower floors of the building. Educational classes, a root cellar and compost units round up the idea of an ecological loop within one building. The farmhouse is an example of a building that is part of our ecosystem. It lives, breaths and grows and is not an island in the city, but integral part to the wider neighbourhood.

Credit: Still Renderings and GIFs by Precht; Animations by Virgin Lemon

Factfile

Project: The Farmhouse

Architects: Studio Precht

Project partners: Chris Precht, Fei Tang Precht, ZiZhi Yu

Project Year: 2017-ongoing

On the night of 1 April, Mumbai revealed her rebellious, punk-inspired side as Vivienne Westwood…

The architectural landscape of Rajasthan is steeped in a rich tradition of historic masonry, reflecting…

Are you a corporate employee spending 10+ hours in an ordinary cubicle that's fused in…

Modern Indian homes are no longer bound by their physical vicinity. They have outgrown our…

Häcker Kitchens, a brand synonymous with quality and innovation, has a rich legacy that spans…

In this home designed by Sonal R Mutha and Aniketh Bafna, founders and principal designers…