We can understand the history of the world by reading architecture.

Harappa’s first ‘civil’ ways of water management tell us about the civilization of humanity. Tribal and vernacular references reveal human needs and tools used for the same. The power of religions is seen by how people metaphorically positioned temples as city centres. The autocracy of the royalty, their forts and palaces showed their prowess and their mindset. From gladiators and their arenas to manicuring gardens and parks as art forms, these are all ways of reading culture through time. Colonisation and the import of everything ‘foreign’ exhibited colonial realities and its deep influence on mind and matter. Building institutions in the Americas and the rebuilding of European cities post wars narrate a tale of industrialization and development. The financial muscle power of the Middle-East expressing itself in its architectural projects is no longer fiction. Perhaps, the (need of) technology and environmentally sensitive architecture of tomorrow must be the reflection of our times.

Harappa’s first ‘civil’ ways of water management tell us about the civilization of humanity. Tribal and vernacular references reveal human needs and tools used for the same. The power of religions is seen by how people metaphorically positioned temples as city centres. The autocracy of the royalty, their forts and palaces showed their prowess and their mindset. From gladiators and their arenas to manicuring gardens and parks as art forms, these are all ways of reading culture through time. Colonisation and the import of everything ‘foreign’ exhibited colonial realities and its deep influence on mind and matter. Building institutions in the Americas and the rebuilding of European cities post wars narrate a tale of industrialization and development. The financial muscle power of the Middle-East expressing itself in its architectural projects is no longer fiction. Perhaps, the (need of) technology and environmentally sensitive architecture of tomorrow must be the reflection of our times.

The built expression builds trajectories that trace history by capturing these curated cultural impressions in time. On a recent study trip to Denmark and Finland, the Scandinavian example really exemplified this. The architecture showed the evolution of the society and defined their attitude of prioritising the planet, while addressing local issues and using regional resources.

However, we do not take responsibility for our fraternity beyond our work as architects.

We use this profession to satiate our creativity and satisfy our clients. This is the most convenient part of the deal. We need to rethink our position as architects and understand how our work shapes society and the impact it has on the planet. Architects are the authors of the manifesto that society writes for itself in a place and at a time. Our work outlives us to speak this and therefore we cannot turn a blind eye to this. There is a need to call out the elephant in the room.

In India, the role of practices, their pedagogy and the people behind them needs to be better understood to awaken a sense of awareness and accountability. Our practices define the cities of today. The architecture therefore reflects the needs of the city, the tastes of the people (self and client), the availability of the technology and material, and perhaps, the state of the economy. This tangibly manifests the intangible culture as well.

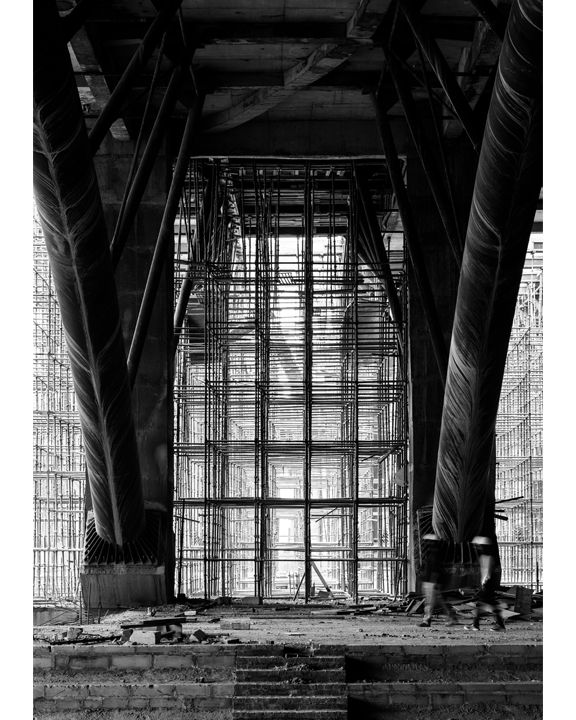

Our public programs of rebuilding old precincts and institutions on one hand, and the speed of infrastructure development to serve the exploding urbanity on the other, gives our times a permanent position and clear filters and tools to curate our morphology. It is therefore vital to understand the role that architecture practices should play in this:

The considerations that need to be looked at, as the basic obligations of an architect.

The priorities we make and the positions we take.

The energy we invest in establishing and expressing our times.

The programs in our projects that we induce.

The forms we emulate. The materials we use.

How we are building narratives and how is the narrative building us.

This Issue of Architecture+Design is therefore dedicated to practices, pedagogy and people, to unfold the ‘raison d’etre’ of our fraternity.

I want to exaggerate and thereby clarify the ‘archetypes’ of Indian architecture practices today. The positions taken by firms due to realities that cannot be ignored, and constraints that need to be respected. We believe there is room for debate that can help all to work within their own means and also push boundaries for the larger whole.

Niche Architecture – They are boutique practices that do great work and are well aware of their obligations. They work within their means and at a pace that they can sustain. However, their work may not scale up to be fully tested for their positions, but they remain within idealistic domains and academic discourse.

Specialists – These are practices that have made a domain choice, usually like landscape, conservation, green building, and they dig deeper within their interest and expertise. They bring in knowledge to the design process with an engineered approach ensuring its deliverance within their scope. Such practices become great team players, but have limited control on the overall project and its direction.

L1 Architecture – These comprise of small and large practices that specialise in government works. They work through tendering processes, obtaining commissions fundamentally based on a highly competitive—read the lowest quoted—fee. Two challenges emerge from this—firstly, the ‘winning’ fee allows them very limited exploration, and secondly, multiple clients (engineers and bureaucrats, and at times politicians) control final design decisions. The position of architects as project leaders is filtered and perhaps at times, compromised. Ironically, these are the largest and fastest projects put in the public domain. It is many times a lost opportunity as it lacks the depth and inquiry of work that could have been achieved but for this democratic bureaucratic process.

2ft Architecture – These are practices that predominantly work for private developers. They work on housing and commercial domains in large city extensions that define the suburban skyline. These practices deal with three issues—one, the footprint where FSI is king and it controls every decision of the built, as it fundamentally maximises profit for the client. Two, the client’s understanding limits the architecture just to primarily be a play on façade, a layer that allows a 2 feet or 600 mm bye-law domain that defines the architect’s playing field. Thirdly, these projects survive on vocalising their supremacy in a competitive environment, where they need to outdo their neighbour.

Parametric and Form Architecture – These are practices that prioritise form over other aspects of architecture. Their inquiry is into developing technology, algorithms and materials that can extend the boundaries of imagination and manifest this reality; in fact, even into the metaverse with its over and ever expanding virtual architecture. This architecture perhaps remains insulated from core issues and starts mostly from the other end of the design process spectrum.

Turn Key Architecture – Architects that do residential or corporate interiors. A large proportion of Indian clientele is not evolved enough to understand and value design and architecture. It is also an unregulated and competitive landscape for all practices. These realities result in a fairly low design fee and therefore, a large number of practices have extended their domain into execution for their clients. This makes the project viable and gives the client a much desired one stop shop solution. The only casualty in this is that design becomes a product that prioritises number crunching and thereby risks mediocrity.

Generalists – They are multidisciplinary architects who choose to not specialise into a specific typology or a scale, nor are they averse to any. They work with a broad philosophy and explore every typology. They are more like ‘jack of all trades’ willing to experiment. Their first principles approach and lack of standardisation usually keeps these practices in a degree of discomfort and instability.

This rather unfair stratification is an attempt to capture the entire landscape of practices and their architecture in India.

It’s fairly hard to decipher a direction that is new and answers the now. Unfortunately, even today, one can still trace relevant Indian architecture with Prof B.V. Doshi, Charles Correa and perhaps Achyut Kanvinde, Joseph Allen Stein and some other regionalists. They are post Independence practices. We are perhaps yet to see promising Indian contemporary practices of today that can stake a claim to be custodians of a new definition. Therefore, the idea of practices and their pedagogical directions becomes a crucial one.

Practices need to take a stand towards architecture in spirit and not mere style. If one had to take the modernism crutch to understand this, CIAM played a big role in such a paradigm shift in Europe. CIAM, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, founded by a coalition of European architects in 1928, was an international forum for new ideas about the urban design of housing and cities in an emerging socio-cultural context. It became a melting pot for various architects to give a certain clarity to a fresh, relevant definition of contemporary architecture for that time.

As architects in India, we still need to take the responsibility to decolonise ourselves and our clients. The desire for Spanish villas, French windows and English furniture requires an overhaul and a reality check. There is a need for responsible, refreshing expression of Indian architecture that must be embedded in our context, our climate, our culture and our times. To imitate is not to express a mark of respect, but the lack of it. Awareness of the West and the past is acceptable, but aping is not. Appreciation of our values and the ability to apply first principles to our indigenous materials, building techniques, while understanding resources and technology available, is vital.

We need conducive conditions from where these broad collective values and directions could emerge. These ideas will always stay conceptual and fundamental, wide enough to not limit any creative expression for anyone. These will be ‘Indian’ and ‘contemporary’ to our times and by us. The solution potentially could be furthered by more focus on the pedagogy of our education ecosystems. The practice of architecture is conditioned by the quality and nature of academia. In the Indian context, academia and practice have been seen as non-overlapping domains—they are placed sequentially and conducted independent of each other in time and physicality (institute versus studio).

Architecture institutes design academic programmes that respond to their vision of the architectural practice. Usually, there are two approaches—the pragmatic and the ideological. In doing so, the conditioning of the practice remains largely incomplete because in essence, practice needs both. The ideation inclined approach falls short while embodying conceptual ideas into physical presences and great ideas get diluted and

lost in translation to reality. Professionals therefore struggle to take ideological positions to address complex issues and thereby their interpretation into

their architecture, the built form.

Indian architectural education needs a more meaningful interface between academics and practice. Professionals need to teach and professors need to practise. Aspirants need exposure and inspiration to be the future of Indian architecture. Therefore, one needs to read architecture by experiencing it, by understanding the masters and their manifestations. Understanding modern masters is a great way to see how a region positions itself with its inherent strengths as well as aligns itself to the world views and values within the architectural fraternity. A case in point, well explained when we recently explored works of two powerful regionalists, Alvar Aalto from Finland and Arne Jacobsen from the Danish fraternity. They both transcended architecture and traversed into larger design domains. From chairs and lights to timeless everyday products, they are an epitome of Scandinavian sensibilities to date.

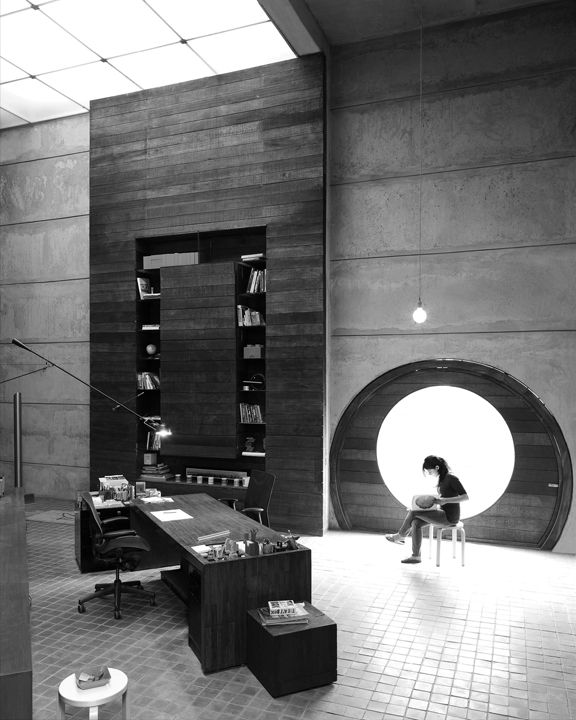

At Archohm, we have attempted to be consistent in our journey of position taking regardless of the typology of work. The nature of work undertaken has made us realise the value of restrain in public architecture. Private projects have given us the opportunity to engage with like-minded clients as well as be on a learning trajectory, pushing the boundaries of a participative process. Our architecture attempts to be context driven, while culture and climate are always the essential starting points. Celebrating the honesty of materials, embracing the local as well as working with state-of-the-art technologies is a constant inquiry. And there is a focus on unravelling the narrative around one’s concept to give the project its meaning. Our approach is experimental and our attitude is collaborative.

The starting point is always on how to address a project if we had no constraints of time and effort; this ensures we get the brightest ideas to the table. Thereafter, limitations are introduced. Client understanding is a bigger obligation than just client satisfaction. This usually takes way more time and resources than allocated. And therefore, come with the pains of energies overinvested and gains of a few worthy battles won. Our practice remains in a state of flux and is always a ‘work in progress’. Losing at times, but hopefully, learning at all times, we remain a tribe on a design expedition.

In our search for contemporary Indian directions, we have tried to instigate dialogue and debate through a few initiatives. The Archoforum workshops help us collaborate on research and projects with international practices with domain specific expertise. We ensure our annual international backpacking exploration of Archotour takes place, despite limited energies. Our monthly newsletter, Archohmeter has been a way to reflect on our work and get feedback for the same. Our institute, The Design Village, is a vehicle that attempts to bridge the aforementioned gap in the education system.

In this issue of Practice, People and Pedagogy, Mridu Sahai Patnaik, co-founder of The Design Village, crafts out a complete trajectory of David Chipperfield Architects’ Berlin office in conversation with their design director, Christoph Felger. It is delightful to see the consistency and clarity with which this practice works across offices and people. Lately, we are working together on researching an archetype of Indian high rises and the journey could not have been more revealing. Architect Madhav Raman gives us a behind-the-scenes account of Indian architecture practices starting from the very genesis of this faculty. Educational Design Strategist Mudita Pasari highlights the pedagogical winds of change and connections one can see constantly in practices. The Scandinavian way of design is outlined by discerning designer Vatsal Agarwal, and a deep dive into master regionalist Alvar Aalto has been penned by Professor Ar. Lena Ragade Gupta. The story of LEGO has come alive by the words of urban design aficionado, architect Akanksha A Thapa, who has just returned from Copenhagen. All these narratives try and stitch philosophy to the people and their practices.

I hope you will enjoy reading the above. One feels fairly vulnerable putting out work and words in the public domain. Therefore, I have taken this as a part of a design journey, a process that helps to articulate and distil one’s inquiries. In the hope that we can take collective responsibility of our fraternity and come together to find a voice of contemporary Indian architecture, we bring in these inconvenient conversations. Let us dream beyond

the reality of what we deliver.

About the Guest Editor

Sourabh Gupta graduated in architecture, from the School of Architecture, CEPT University at Ahmedabad in India. With the insight provided there by the best in the realm of architecture, coupled with a stint in urban design from the architecture school at TU delft, the Netherlands and most importantly, propelled by a compulsive need to travel, explore and design, Sourabh initiated Studio Archohm.

Having won and executed a series of design competitions and commissions, Archohm has grown in leaps and bounds in the last decade and a half. Today, its portfolio has a stimulating mix of typologies, scales and sectors of architectural works, infrastructure, furniture and product design, design research and system design. Having transcribed a full circle with its own design education and publication extension, it strives to be a one-stop-shop for almost everything in the world of design.