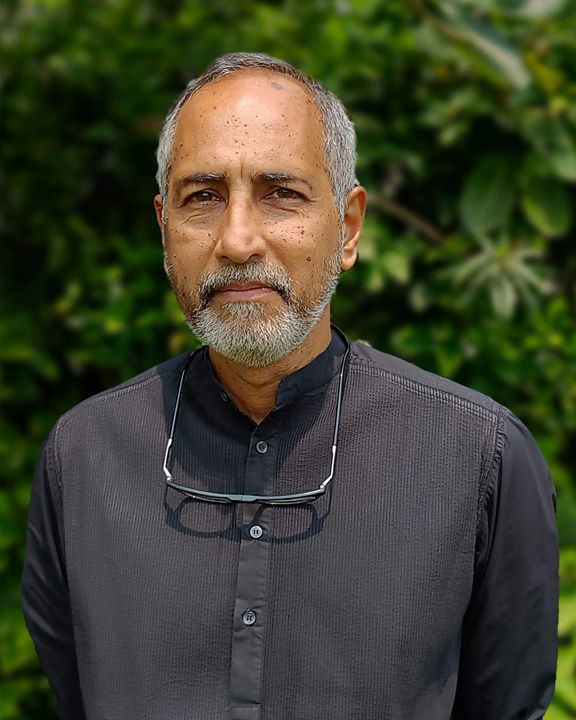

Rahul Kadri is a Partner & Principal Architect at IMK Architects, an architecture and urban design practice founded in 1957 with offices in Mumbai and Bengaluru. He holds a graduate diploma in architecture from the Academy of Architecture, Mumbai, and a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Michigan, USA. Architecture and design always exist within a larger urban, social and ecological milieu. And as a practitioner, one must be conscious of this context and respond to it in a manner beyond just the tectonic or aesthetic structuring of spaces and elements.

Within large-scale master-planning and housing projects, this understanding of the intricate relationship between man and environment assumes critical relevance. How does a building or a series of buildings interact with the city? How do they relate to their immediate built or unbuilt surroundings? What are the natural energies available and how can they be tapped? Can architecture help shape neighbourhoods and promote community interaction? Can it influence health, behaviour, and patterns of living? What do people really value? What makes them happy? How can we create places where people thrive?

Planning for Self-Sufficiency

Imagine a neighbourhood where you could access everything you need within a 500-metre radius from your doorstep — a self-sustaining unit with all public facilities and amenities available locally, from schools and hospitals to gardens and weekly farmer markets; a unit that could be administered with ease and where inhabitants would be able to walk or cycle to work, to learn, to shop, and to play.

staggered to create linear corridors of open spaces between that act as intimate landscaped areas for interaction; Photographs by Hemant Patil

This principle is the foundation of all our work on campuses and townships; our architects identify a centre and plan all non-residential needs of the community within a walkable distance. Such ‘smart neighbourhoods’ reduce travel times and the need for regular inter-neighbourhood journeys, and by corollary, the high levels of carbon emissions and pollution in our cities today. They also ensure optimisation of resources and services, reduce wastage, and ensure effective costing.

Living in a Forest

Research shows that humans have an innate affinity with the natural world — a concept known as biophilia — and that the presence or absence of the elements of nature within our homes, offices, or schools, has a direct and measurable impact on our health and wellbeing. Our aim, therefore, is to always design spaces that are in harmony with their natural context.

This can be achieved through optimal orientation of buildings to allow for natural light and ventilation; by building within the tree line, and creating connected green, open spaces and pedestrian corridors; and by providing spaces for occupants to grow their own food in private kitchen gardens or collective urban farms.

Fostering Interaction

We aim to design communities that are dense enough to not only utilize resources and infrastructure effectively but allow people to be close to each other. To that end, we consciously design open, interactive spaces of varying sizes and scales for all kinds of users across age groups — from casual sit outs and smaller spaces for children to play to larger open grounds for sports and other recreational activities. This fosters community interaction and relations between neighbours and their families, leading to a sense of ownership and belonging and creating neighbourhoods that are filled with energy.

Eyes on the Street

Jane Jacobs’ concept of ‘eyes on the street’ is one of the cornerstones of modern urban theory — vibrant street life is a crucial benchmark of perceived and real security within a neighbourhood. Maximizing perpendicular street junctions helps slow down traffic and create focal points of interest at such nodes in the form of plazas and landscaped spaces.

Designing for Sustainability

Sustainable neighbourhoods meet the diverse needs of existing and future residents, are sensitive to their environment, and contribute to a high quality of life. They are safe and inclusive, well-planned, -built and run, and offer equality of opportunity and good services to all. We approach sustainable design through the lens of the local context of the region. Our design for the built and the open takes from indigenous building materials, architectural language and climatic considerations. Our approach hinges on looking at sustainability from a holistic standpoint.

Cultural Sustainability: Cultural sustainability focuses on the amenity of place. Put simply, if people are happy and enjoy their life, they will stay. Therefore, it is important to look at the complete life cycle from infancy to retirement, for families and single people. Designing a diversity of spaces is the key to making a place enjoyable.

● Education facilities for all ages from pre-schoolers to adult education.

● Places for people to socialize from restaurants to neighbourhood parks.

● Quiet spaces for people to relax as well as lively spaces with a lot of activity.

● A diversity of entertainment options for people of different socio-economic levels.

Economic Sustainability: A town cannot be sustainable without a stable economic base where wealth grows and opportunities are varied. A diversity of buildings, opportunities and businesses, therefore, is imperative to success.

● Entrepreneurship is to be encouraged, with a range of options: working at home, live-work units, and larger corporate or manufacturing spaces to facilitate future expansion.

● Educational facilities are to be provided to help in personal development and the promotion of other businesses.

● Retail spaces, both regional and neighbourhood, attract regional spenders to contribute to the local economy for longer.

neighbourhood, which would promote social engagement and a sense of belonging; Photographs by Rajesh Vora

Environmental sustainability: Environmental sustainability aims at conserving and/or efficiently utilising energy and water and contributes towards slowing down cataclysmic global effects.

● Minimising the impact on the natural topography by building along the contours and retaining natural storm water drainage systems.

● Adopting sustainable water management and recycling across the township as well as the JSW steel plant.

● Recycling of waste.

● Introducing flora to control local climatic issues such as adding trees for shade.

● Conserving the natural plant and wildlife for future generations.

● Sustainable architecture in terms of materials, energy use, shading devices and long-term adaptability.